RESEARCH

Energy Transition Investment Strategies that Decarbonise the Real World

Guidelines for Institutional Investors

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing policy must be, in principle, a good idea for all investors to the extent that incorporating potential E, S and G impacts into the evaluation of investment opportunities may help investors avoid negative surprises or to spot investment opportunities. But the term ESG takes on many different meanings with different investors. We find our investment recommendations are clearer when we separate the E from the ESG and specifically discuss the impact of the energy transition on different asset classes, sectors and companies. This is not intended to suggest that other impacts covered under the S and G are less important, but rather that it is more effective to discuss the specifics of each separately.

This note focuses solely on guiding institutional investors in the development of their own policy or plans for investing in and around the energy transition and applies to allocations within all asset classes, but mostly within public and private equity. Each of the energy transition strategy options presented here refers to public equity examples but generally apply to private assets as well.

Why does any investor need a policy for investing in the energy transition?

The future cost of carbon abatement is likely to have a very material impact on approximately 25% of the asset value of public and private equity markets. More specifically, the industrial, energy, materials, utilities and transportation sectors of the public and private equity markets comprise approximately 25% of the value of market capitalisation in the developed world, and account for nearly 90% of emissions.

Exhibit 1: 90% of public company emission (scope 1 & 2) are derived from five sectors (adding in the automotive sector) which account for 25% of the market capitalization.

Source: Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA. Booth School of Business, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London, UK. Business School, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany. August 2023 issue of Science magazine. In December 2023, the EPA updated its social cost of carbon to $191/tonne which attempts to include the climate’s response and costs of measures to adapt to rising sea levels and higher temperatures. $51/tonne represents the Biden administration’s cost announced in March 2021. $100/tonne represents the midpoint in the Goldman Sachs analysis of the cost of carbon abatement across all sources of emissions as published in Carbonomics (2023). The research study only included $51 and $191/tonne calculations. Partners Capital interpolated the profit impact of $100/tonne cost of abatement.

Assuming the average cost of carbon abatement will be approximately $100 per tonne, this suggests that most companies operating in these sectors will see their valuations changing materially as they invest in lower carbon products or processes or choose not to.

Exhibit 2: A $100 price of carbon materially reduces the profitability of the majority of US energy, materials, transport, utilities, and food companies.

Source: Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA. Booth School of Business, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London, UK. Business School, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany. August 2023 issue of Science magazine. In December 2023, the EPA updated its social cost of carbon to $191/tonne which attempts to include the climate’s response and costs of measures to adapt to rising sea levels and higher temperatures. $51/tonne represents the Biden administration’s cost announced in March 2021. $100/tonne represents the midpoint in the Goldman Sachs analysis of the cost of carbon abatement across all sources of emissions as published in Carbonomics (2023). The research study only included $51 and $191/tonne calculations. Partners Capital interpolated the profit impact of $100/tonne cost of abatement.

Given the materiality of this impact on asset values facing a quarter of the stock market and a similar proportion of the private equity market, investors have had to establish, document and execute investment strategies to address the risks and opportunities of the global energy transition. Ignoring the energy transition and not having a deliberate plan to deal with the transition is an option, but one that has the investor defaulting to having the sum of the actions of its asset managers somewhat randomly determine an institution’s energy transition investment strategy. It is our view, based on years of deep interactions with asset managers and from the Partners Capital annual ESG manager survey, that most public and private equity managers do not have sufficient knowledge or expertise on the range of scenarios for how the energy transition will play out and impact the value of companies under each of those scenarios.

We recommend that any good energy transition investment policy starts with the assessment of each asset manager’s understanding of the energy transition and takes a view on whether their capability is sufficient to avoid the risks and exploit the opportunities presented by the global energy transition. Beyond this process of manager energy transition capability assessment that should be undertaken every year in the institutional investor’s manager ESG survey process, we suggest that every institutional investor will add needed clarity to their day to day investing if they have in place a clearly documented energy transition investment strategy along a spectrum from a passive approach to one that is actively seeking to move the portfolio to one that owns companies with low or no emissions – i.e., a Net-zero policy.

Energy Transition Investment Strategy Options

Many large institutions already have very clear and articulate energy transition strategies, but under various headings such as sustainable investment policy or climate action plans. We draw your attention to several excellent examples including those of GIC, the Norges sovereign wealth fund (NBIM) and Cambridge University. But many institutions do not have a policy in place today or that policy is implicitly a passive one that is in effect the sum of the policies of the underlying asset managers, where third party managers are deploying the bulk of the capital.

We firmly believe that all dedicated long-term investors should develop and articulate a well-defined strategy for investing in the energy transition. This can be guided by the various Energy Transition Investment Strategy (ETIS) approaches outlined below, which are complementary and can be blended in different ways.

ETIS #1: The default energy transition investment strategy has the investor accepting the risks of owning companies in the highest emitting 25% of the market and trusts that most of their existing active asset managers are engaging in very deep analysis of the optimal decarbonisation pathway for each high emitting sector and the companies within them. Their ongoing analysis seeks to identify those companies best positioned to tackle the energy transition risks and exploit the largest opportunities. This may result in a total portfolio over or under-weight allocation to high emitting sectors and to the “green companies” acting as the biggest enablers of decarbonisation, depending on the collective views of all of your asset managers.

ETIS #2: Exclude strategy. This strategy aims to mitigate the risk of holding companies most vulnerable to the impacts of the energy transition. Proponents of this approach have different underlying beliefs for adopting it, some on more grounds and some driven by genuine concerns about unanalysable risks. Those believe that the costs of carbon abatement or taxation may not be fully reflected in current company valuations. As a result, they choose to exclude one or more high exposure sectors, such as energy, industrials, utilities, materials, and transportation. This strategy allows for flexibility in its implementation, ranging from narrow exclusions focused solely on coal, oil and gas, to broader exclusions that encompass other high-emitting industries like utilities, steel, cement, aviation, shipping, automotive, and materials.

Divestment has the unfortunate consequence of defunding decarbonisation. Mark Carney set up GFANZ to ensure we have the financial funding for decarbonisation. The GFANZ (Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero) team would find the biggest boost to decarbonisation finance from encouraging institutional investors to back the biggest public company emitters in their investment strategies. This may go further than any other global action toward financing the global energy transition. To the extent the majority of that financing is expected to come from the large emitters (industrials, automotive, electric utilities), excluding them from the portfolio is potentially making it more difficult to fund the most important and economically viable means of decarbonisation.

Investors following the exclusion strategy have to accept the potential for tracking error relative to all-industry benchmarks like the Cambridge Associates PE benchmark or the MSCI World equities benchmark. In essence, exclusion strategies explicitly accept the risk that excluded sectors may outperform the broader market.

Many private and public equity managers today already exclude coal, oil and gas companies, but few go so far as to exclude the other high emission sectors. The “exclude” strategy is best implemented with passive ETFs, index funds or segregated accounts where the investors can be certain of what companies or sectors are included or not.

ETIS #3: Engage with Corporate Management. This involves investing with activist asset managers focused on the energy transition, who have deep expertise around the optimal decarbonisation strategies for each of the major emitting sectors. For the largest of institutional managers, like GIC and NBIM, who invest directly in the broad equity market, they have long had the ear of management and have long had dialog with corporate management on their energy transition plans. The aim is to get management to understand the long-term shareholder value improvement that may come from being early to decarbonise in their sectors. Activist manager, Engine No. 1, gained major attention in 2021 when it successfully Energy Transition Investment Strategies that Decarbonise the Real World 5 launched a campaign to replace several board members at ExxonMobil, advocating for stronger environmental strategies and a transition toward renewable energy. While not strictly an activist firm, Generation IM is another public equity investor who advocates for climate risk integration into corporate strategies.

Our concern over the engagement strategy is that rarely do institutional shareholders have the depth of understanding into the full economic impact of various alternative strategies that any one company has to choose from for long term decarbonisation. But activists who listen and learn from transparent management teams, may convince management that shareholders may not only tolerate, but encourage the short term hit to earnings in favour of the long term decarbonisation benefits that may enhance long term shareholder value. It may well be that shareholders with a focus on quarterly earnings are the source of the schism between management and execution of the optimal long-term decarbonisation plan.

ETIS #4: Energy Transition as an explicit investment theme. Here, the investor deliberately allocates a specific proportion of total portfolio assets to specific sectors and companies most influential to the energy transition through generalist and specialist asset managers. Energy transition focused managers seek to back companies with the greatest potential to reduce carbon emissions including both the “Enablers” of decarbonisation (e.g., solar, wind, battery and EV companies) and the “Improvers” or largest industrial decarbonisers (automotive, chemicals, steel, cement, utilities, etc.). Most energy transition equity and private equity managers focus most on the enablers or solutions, and shy away from the improvers, presumably on the basis of risk that is highly difficult to analyse. Specialist managers include Clean Energy Transition (CET), Encompass, Covalis, Goodlander, Pictet, Blackrock and many more. Most large asset manager houses will have a specialist energy transition strategy among their funds, most focused on enablers.

Enablers are companies involved in the production of clean energy or provision of clean energy technology and equipment. The S&P Global Clean Energy Index (CLEN) includes all major constituents worldwide that meet this criterion and includes 99 companies with average market capitalisation of $8B, representing almost $800B of potential investments or 0.7% of the global $120T equity market. Returns averaged 5.3% over the last 10 years with annualised risk of 26.7% for a Sharpe ratio of 0.12. This compares to the global average (MSCI World) of 9.6% average return and a 15% standard deviation, or a Sharpe of 0.5. Clearly broader definitions can be used, but Enablers will still comprise a relatively small portion of the global equity market for some time with highly volatile performance, presumably driven by the large number of specialist funds investing in a relatively limited universe.

Improvers include any company that is not an Enabler and excludes companies with largely stranded assets (e.g., most coal, oil and gas companies) on the basis that there are practical limits to their ability to fully transition to low carbon emitting companies. This leaves the vast majority of the global equity market companies facing an energy transition to one degree or another. Approximately 70% of global emissions are concentrated with 17% of the global equity market (~$20T) comprising industrials, materials and utilities (the difference from the 25% discussed above being the coal, oil and gas sectors. Most of the potential Improvers are found in these sectors including companies like Holcim in cement, Arcelor Mittal in steel, AP Moller in shipping, and Linde in chemicals. Returns over the last 10 years have averaged 7.3% with a standard deviation of 13.7% for 0.39 Sharpe. Improvers comprise companies who account for the vast majority of the nearly $2T a year invested in global decarbonisation.

In our opinion, any good public equity strategy focused on exploiting opportunities presented by the energy transition, will have both improvers and enablers in their universe of investible companies. The right asset managers will have deep insights into the technology and economics of the enablers of the energy transition and they will have developed the most economically effective decarbonisation pathways for each subsector of the Improvers such as cement, steel, automotive, pulp and paper and electric utilities. This is not a strategy of simply owning the biggest emitters or decarbonisers, but rather seeks to own those companies where the current valuations do not accurately reflect all the technological, regulatory, economic and customer behaviour inputs to a company’s most likely transition strategy. This involves deep insights into the capital and operating cost of lower carbon processes and products and the likelihood of being able to pass such costs on to the customer earning the so-called “green premium.” In some cases, paying the carbon tax may be less expensive than investing in lower carbon processes. The improver investment strategy simply seeks to own the company where the Energy Transition Investment Strategies that Decarbonise the Real World 6 management team are following the highest shareholder value path to decarbonisation which may include buying carbon credits, paying the taxes or disposing of “stranded assets.”

Alpha will not be generated solely through an understanding of decarbonisation. It will emerge from marrying this understanding with a deep knowledge of all sector dynamics, the relative positioning of companies, and the sequence of likely outcomes as technology and cost structures evolve, all translated into long-term cash flow forecasts discounted to the present to be compared to current valuations.

Allocations to this strategy will be mostly guided by the availability of high conviction managers who understand both the enablers and improvers, with the default allocation being at weight to the sectors involved. Over-weights to this strategy should be in proportion to expected alpha. We presume the investor is unwilling to accept risk-adjusted returns that fall short of what is expected from the asset class more broadly, so any overweight would be in the belief that the alpha would compensate for tracking error over the long-term, but the energy transition impact would be greater. This thinking is no different that any over-allocation to a sector specialist in public equities.

Many asset owning institutions focus their over-weights solely on the enablers of the energy transition and avoid the high emitting companies. As described above, the cleantech sector represents a small and volatile 0.7% of the global equity market, while the major decarbonising sectors account for approximately 17% of the global equity market as we show in Exhibit 1 above. Investors concentrated their energy transition investments in the enablers in recent years have suffered poor returns as they included smaller tech companies which experienced bubble formation and bursting cycles. On the other hand, the improvers tend to be in the most highly cyclical sectors, but with much lower volatility experienced than for the green sector of enablers.

Sovereign wealth fund, GIC (Government of Singapore), publishes its approach to sustainable investing which contrasts with a rigid, top-down strategy that divests from entire industries without considering their individual circumstances or potential for positive change. GIC emphasises contributing to real-world decarbonisation, rather than focusing solely on portfolio decarbonisation (i.e., exclusion or divesting).

Investors like GIC who are pursuing the goal of real world decarbonisation, as opposed to portfolio decarbonisation, will set milestone goals in the form of total tonnes of GHG emissions reduced and avoided over time by the companies owned, including scope 1 and 2 emissions for most sectors, but adding scope 3 for automotive and certain engineering companies (e.g., manufacturers of gas turbines).

Exhibit 3 below summarises the options laid out above. These options are by no means an exhaustive list of potential energy transition investment strategies. However, we firmly believe that investment performance can be materially positively impacted where the investing institution’s investment committees or other decision makers take the time and mental energy to arrive at the best strategy for their portfolio.

All four strategies below are relevant to how allocators invest in public as well as private companies.

Exhibit 3: Energy Transition Investment Strategy Options: There is no one “most sensible” way to invest. Investors benefit from taking a clear view on which approaches best fit their investment objectives.

A Pragmatic approach to Net-Zero emissions goals for investors

Net-zero goals apply to countries, companies, asset managers and asset owners. It is not controversial that countries and companies should set net-zero goals and design and implement plans to achieve those. The decarbonisation plans of the largest emitting companies will most powerfully drive the global energy transition. The virtue of net-zero goals for investors is controversial. Currently, about 53% of European pension funds have committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions in the companies they hold in their portfolios by 2050. A smaller portion of pension funds have set more ambitious targets: 14% aim for net-zero by 2035, and 18% target achieving this by 2040. The U.S. pension industry is gradually aligning with global efforts, with some leading funds targeting 2040, while many aim for 2050. However, U.S. pensions generally trail behind European funds in net-zero commitments.

There are two ways institutional investors and asset managers think about net-zero goals — my portfolio holds no companies with carbon emissions or my investing activity creates real world decarbonisation.

Net-zero achieved by decarbonising my portfolio: When Net-zero goals were first being embraced by investors, the thinking was that if the investor divests from carbon emitting companies, this can accelerate their extinction and accelerate decarbonisation as a result of raising their cost of capital and discouraging talented management from working for them. But we reiterate that divestment has the unfortunate consequence of defunding decarbonisation.

Net-zero achieved by contributing to real world decarbonisation: As with all new things in the investment world, investment thought leaders have evolved their thinking about net-zero goals after more careful thought and some recently published research on the negative impact of exclusion on emissions. Two examples of constructive policies focused on real world decarbonisation are described below.

The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund manager NBIM states in their 2025 Climate Action Plan, “at the heart of our efforts is driving portfolio companies to Net-zero emissions by 2050 through credible targets and transition plans for reducing their scope 1, scope 2 and material scope 3 emissions…. We believe that companies that understand the drivers of Net-zero emissions and anticipate regulatory developments will be well-positioned to capture the financial opportunities arising from a low-carbon economy. While some high-emitting companies may decline in value, others will transform their business models and grow among the greening companies supporting an orderly transition…. We believe that our engage-to change approach will yield the best financial results for the fund. It will also contribute to improved real-world outcomes…. Working towards a Net-zero 2050 target for our portfolio companies gives a strategic direction for all our climate activities.”

The Singapore sovereign wealth fund, GIC, states in their Sustainable Investing Strategy, “While portfolio decarbonisation can be achieved through divestment, GIC prioritises tangible impact in the real world.”

These two examples manifest a combination of all four strategies above. GIC, for example, excludes assets they deem to be “stranded assets” which are assets with a high risk of becoming obsolete due to their high carbon intensity which they estimate to be 10% of the MSCI. They invest in “green assets” which represent about 7% of MSCI. The remaining 83% are all considered to be “transitioning assets” which includes what we refer to as “improvers” above but also companies in low emitting sectors. “GIC engages with transitioning companies to understand their transition plans, assesses the viability of supporting their transition with capital, and evaluates the risk/reward profile of such investments.”

A net-zero portfolio policy proves to be impractical over anything other than a very long time frame. A short time frame forces the investor to sell the largest emitters before they have been able to make all of the investments required to transition to low emission products and processes. Selling early on may have the effect of raising the biggest potential decarbonising companies’ cost of capital and discourages the best management teams from joining such companies to manage the most effective decarbonisation plans.

This is how that works. The average carbon intensity as measured by CO2 equivalent tonnes of carbon per million dollars of market cap is approximately 80 tonnes/$1M market cap. A net-zero portfolio needs to get to 0 tonnes/$1M market cap, usually set for 2050. Targets set too early relative to what the real world can achieve, forces sales of high emitters (e.g., electric utilities, steel companies) which are among the biggest investors in the energy transition. A better set of interim metrics would be to measure the real-world reduction in emissions by the companies during the period of ownership with ambitious targets set for that metric. This focus on real world decreases in emissions by the companies owned, motivates the asset owner to engage with that company and to make sure the companies owned are those who appear to be maximising shareholder value through the right decarbonisation plan for that company.

The most pragmatic net-zero investment strategy involves taking a long-term investing time frame and investing with asset managers who are ahead of the pack in terms of understating the best decarbonisation pathways for each industrial sector, measuring the change in emissions at the company level, to see real world decarbonisation, not portfolio decarbonisation. These managers may also have the capabilities required to effectively engage with management teams on their decarbonisation strategies.

Energy Transition Strategy Options in Private Equity

The 4-strategy framework perhaps holds more relevance to public equity investing than it does for private equity. The energy transition has rapidly become a major segment of the venture capital and private equity investment universe which is the subject of a future TNI publication. The four options shown in Exhibit 3 have long been the focus of private equity investors, but reaching a major inflection point as measured by AUM raised right through the Covid years of 2020 to 2022. The exclusion strategy came to many oil and gas investors like Blackstone, SCF, ARC, Riverstone and SCF as LPs sought to avoid fossil fuel investments. This had most resources-sector focused PE firms migrating their businesses to all but exclude fossil fuel investments, now focusing on the broader energy transition opportunity set including both enablers and improvers. Energy Transition Investment Strategies that Decarbonise the Real World 9 Engagement on energy transition strategies in more gradually becoming a source of value added from private equity owners. Specialist power sector focused buyout firms like Oaktree Power and LS Power have long ago moved into renewable electricity businesses, helping the electricity industry decarbonise, which represents companies who are deploying enabling technologies to move from being brown to green companies (i.e., improvers).

Large buyout and growth equity firms like TPG, Apollo, KKR and General Atlantic have launched ESG funds with large allocations to energy transition investments.

All of the major infrastructure firms including Macquarie, Brookfield, Stone Peak, GIP/Blackrock and ACTIS have relatively longer track records in renewables and other energy transition infrastructure.

Approximately 12% of all venture capital is now invested in cleantech deals, the vast majority being major enablers or solutions for the energy transition including investments in nuclear, clean hydrogen, clean industrial process technology, geothermal, bio-energy and long-duration energy storage, having moved beyond earlier technology breakthroughs in EVs, solar, wind and batteries.

How should institutional investors set goals for overall portfolio asset allocations to the Energy Transition?

The energy transition is an investment theme primarily limited by the availability of high-caliber specialist managers who possess the expertise needed to navigate inefficiencies in the market created from uncertainty around how technology, regulation, and customer behaviour will ultimately impact asset values. This approach is no different from how investors approach sectors like life sciences or emerging tech, relying on niche insights to gain an edge. With full awareness of the risks, and our familiarity with a small universe of deep energy transition focused equity managers, we embrace a modest overweight to energy transition sectors, anchored in the belief that specific generalist and specialist managers can deliver meaningful alpha. This recommendation assumes that the investment policy does not mandate specific impact targets and prioritise the energy transition as a central theme for that reason.

Where there is an explicit impact goal, as is the case with many family offices with whom we share views, allocations may be made with so-called concessionary return targets, but with the right asset managers, we do not see that as a necessary condition for an overweight allocation to the energy transition theme.

Epilogue

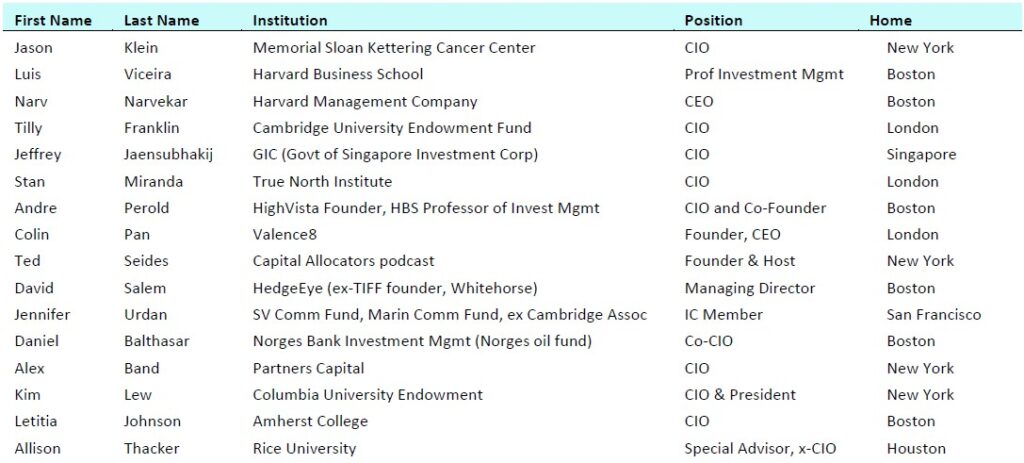

This whitepaper is the second iteration after being reviewed by a group of 15 CIOs who were convened in a conference hosted by the True North Institute in the Boston offices of Partners Capital on the 7th of November, 2024. Those CIOs emanated from two of the largest sovereign wealth funds, several large US and UK university endowments, three OCIOs, and two Harvard Business School professors of investment management. The appendix summarises their observations from their own experiences from investing in the energy transition.

6 December, 2024

True North Institute

Summary of 7 November 2024 TNI CIO Forum discussion on Energy Transition Investment Policy

Below, we summarise the main conclusions form the CIO Forum workshop.

True North Institute CIO Forum Contributors

Alignment on Energy Transition as a Key Issue: There is a broad consensus among the CIOs that the energy transition is a significant investment consideration. While US-based investors may have it lower on their priority list compared to non-US investors, it remains a top concern for most.

Disagreement on Urgency and Impact: There are differing viewpoints on the immediacy and potential impact of the energy transition. Some CIOs see it as a major driver of asset values but are uncertain about the timing and effectiveness of government policy actions affecting the cost and pace of carbon abatement. Others view it as a gradual evolution rather than a disruptive transition.

Lack of Board Alignment: A common challenge is the lack of alignment between investment teams and their boards regarding the energy transition. This misalignment often stems from a lack of board member familiarity with the many nuances of the energy transition and/or from the need to appease various stakeholders. Working sessions with board members and investment team leaders on the topic was presented as a practical solution.

Need for Asset Manager Education: Many CIOs believe asset managers require further education to effectively navigate the risks and opportunities of the energy transition. Some argue that most asset managers lack a deep understanding of its economic impact on companies.

Divestment Not a Solution: Divestment from fossil fuels is widely viewed as an ineffective strategy. Most CIOs believe it simply shifts the problem to other investors without addressing the underlying issue of real-world decarbonisation.

Focus on Engagement and Transitioning Companies: The preferred approach is to engage with companies to encourage their transition to more sustainable practices. Investing in companies with viable net-zero plans and actively using shareholder voting power to drive change are key strategies.

Investment Opportunities Require Further Evaluation: While the energy transition is recognised as an important investment theme, the attractiveness of specific opportunities is still under debate. The discussion leaned in favour of private investing in the energy transition, feeling the opportunities were more tangible, while public equity strategies with clear alpha opportunities were less frequently crossing the CIOs’ desks. But even in private equity, CIOs find it challenging to identify options that stack up against private investments in other sectors.

This final comment coming out of the conference points to the mission of the True North Institute. Our mission is to scour the investment universe to find those investments which deliver outperformance from deep insights into the most economically attractive means of decarbonisation. It is our belief that decarbonisation will occur where the largest profit pools are being formed to support it.